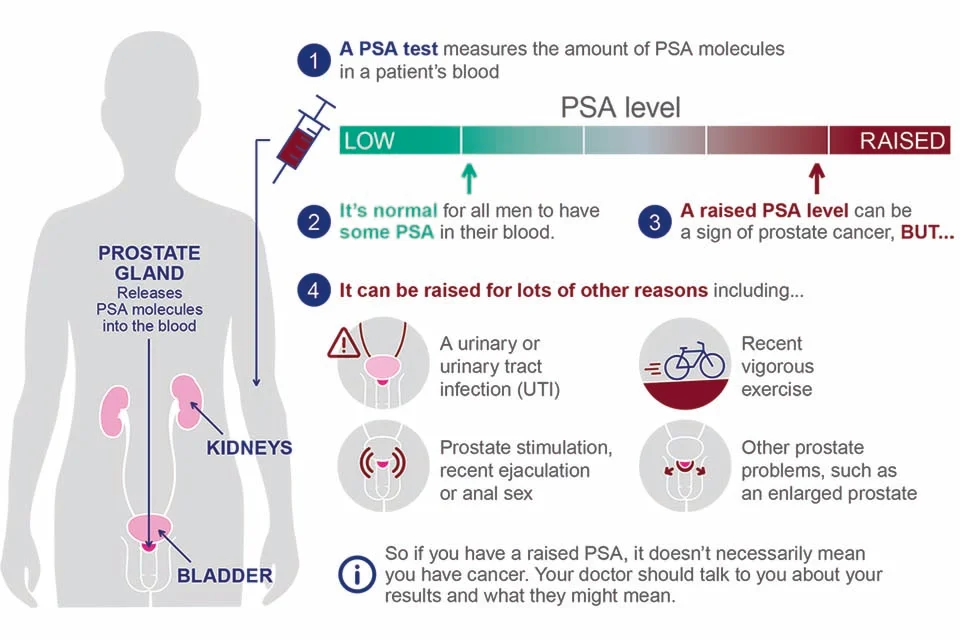

What is a Dangerous Psa Level After Prostate Removal? After a radical prostatectomy (complete removal of the prostate due to cancer), the level of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in the blood should drop to a very low or undetectable level. Because PSA is produced almost exclusively by prostate cells (benign or malignant), when the gland is removed, PSA production should virtually cease.

However, some PSA may persist for a short period post-surgery due to remaining microscopic prostate tissue or delayed clearance from the bloodstream. That’s why tests are usually deferred for some weeks. The first reliable PSA measurement is often taken about 6 to 8 weeks after the operation

A truly undetectable PSA depends on the sensitivity of the test. Some ultrasensitive PSA assays can detect levels as low as 0.01-0.05 ng/mL, while more standard ones might detect down to 0.1 ng/mL or slightly higher. What matters is whether PSA is “undetectable” by the test being used, and whether it remains low on follow-up tests.

Defining “Persistently Detectable PSA” and Biochemical Recurrence

After surgery, two terms are important:

- Persistently detectable PSA: when PSA does not fall to undetectable (or very low) levels in the early postoperative period. Often defined as PSA ≥ 0.1 ng/mL measured about 6 weeks after surgery. This may suggest there’s still residual prostate tissue or early cancer left behind.

- Biochemical recurrence (BCR): when PSA, having once been very low or undetectable, rises above a certain threshold on at least two consecutive measurements. This indicates likely recurrence of prostate cancer (locally, in residual prostate bed, or less commonly distant metastasis).

What thresholds define BCR vary slightly by guideline, but many clinical protocols use PSA ≥ 0.2 ng/mL (with confirmatory repeat test) as the cutoff point

What PSA Level Is Considered “Dangerous” After Prostatectomy?

The word “dangerous” in this context refers to a PSA level that suggests likely recurrence of cancer, or residual disease that might need additional treatment (such as radiation or hormone therapy). Several levels are particularly noteworthy:

| PSA Level | Interpretation / Risk | When Clinicians Typically Consider Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Undetectable (or very low, e.g. < 0.05-0.1 ng/mL) | Optimal outcome. Suggests successful removal and no obvious residual disease. Low risk. | Routine periodic monitoring. No immediate therapy. |

| Persistent PSA ≥ 0.1 ng/mL (early post-op, ~6 weeks) | Risk factor for future recurrence. In studies, those with ≥ 0.1 ng/mL early had worse PSA-free survival. | Closer monitoring; consider early salvage therapy depending on other risk factors (margin status, pathology). |

| PSA rising above ~0.2 ng/mL on two consecutive tests | Widely used definition of biochemical recurrence. At this level, the probability that cancer has recurred is significantly increased. | Usually triggers consideration of salvage radiotherapy, imaging to locate recurrence, and possibly additional therapy. |

| Higher levels (≥ 0.4-0.5 ng/mL or more) | Suggests more substantial residual disease. The higher the PSA, the greater the risk of progression to metastasis if untreated. | Likely need more aggressive evaluation and treatment. May guide earlier imaging for metastasis. |

So, in many guidelines, a PSA of 0.2 ng/mL or more, confirmed, is considered a “dangerous” level because it defines biochemical recurrence and often prompts action. Levels higher than that, especially rising rapidly, represent greater concern.

Other Factors That Modify “Danger”: Rate, Pathology, Time

PSA level alone isn’t the only factor—risk depends also on how fast PSA is rising, the pathology of the cancer, and how soon after surgery the rise appears.

- PSA Doubling Time (PSA-DT): how quickly PSA doubles. A shorter doubling time (e.g. ≤ 6 months) is associated with more aggressive disease and worse prognosis.

- Gleason Score / Grade / Pathologic stage: more aggressive histology (higher Gleason, extension beyond the prostate capsule, positive surgical margins, seminal vesicle invasion, lymph node involvement) raise risk.

- Time to recurrence: if PSA rises very soon after surgery (persistent PSA or early PSA elevation), risk is higher; later recurrence tends to have a slower course.

All these modify what level of PSA is considered “dangerous” in a given patient and when to intervene.

Guidelines and Recommendations: When to Take Action

Medical guidelines provide frameworks to decide when PSA levels after prostate removal are concerning enough to require further diagnostics or treatment:

- According to American Urological Association (AUA) and European Association of Urology (EAU), biochemical recurrence (after radical prostatectomy) is generally defined by PSA ≥ 0.2 ng/mL confirmed with a second measurement.

- Some researchers argue for earlier thresholds. For example, evidence suggests PSA ≥ 0.1 ng/mL relatively soon (e.g. 6 weeks post-op) is a risk factor and may merit earlier salvage radiotherapy.

- Timing of PSA testing: first post-operative check at 6–8 weeks, then every 3 to 6 months in the first couple of years, then annually if stable.

Decisions for salvage treatment (radiation ± hormonal therapy) often balance PSA level, doubling time, patient health, side effects, and pathology.

Implications of High PSA Levels: What Is “Dangerous” in Practice

When PSA levels reach levels considered dangerous, there are important implications for prognosis and potential treatment:

- Salvage Radiotherapy (SRT): If PSA is rising (≥ 0.2 ng/mL or earlier in some plans), radiotherapy to the prostate bed may be indicated. Early SRT, when PSA is still low, tends to lead to better outcomes.

- Imaging: At higher PSA or rapidly rising PSA, advanced imaging (e.g., PET scans, MRI) may be used to locate recurrence. Lower PSA means imaging is less sensitive, so timing matters.

- Risk of metastasis: The longer untreated recurrence persists, the more likely disease can spread locally or distantly. Higher PSA, rapid doubling, or high Gleason increase this risk.

- Patient monitoring & follow-up: More frequent PSA tests, closer statistical modeling, and possibly interventions are needed. Patient preferences, life expectancy, and potential side effects are considered.

What “Undetectable” Means and When Slight Elevations May Not Be Immediately Dangerous

Not all PSA elevations post-prostatectomy mean serious recurrence. Some caveats:

- A PSA reading slightly above the assay’s detection limit (e.g. 0.05, 0.1 ng/mL) may represent residual benign prostate tissue, or very small amounts of prostate cells not necessarily malignant.

- Some PSA assays are more sensitive (ultrasensitive PSA tests); these detect very low levels that older tests might miss. With those, very low levels (< 0.1 ng/mL) are often expected early on; what’s more important is whether levels are stable or rising.

- PSA can fluctuate slightly due to lab variability or minor technical issues. That’s why guidelines require confirmatory testing for biochemical recurrence.

Summary: What PSA Level Should You Watch Out For?

Putting it all together, here’s a summary you can use (always in context with your own medical team) to know what level of PSA post-prostatectomy is potentially dangerous:

- Ideal: undetectable PSA (or very low within the test’s limits) at ~6-8 weeks post-surgery.

- Early Warning: PSA ≥ 0.1 ng/mL soon after surgery (persistent detectable PSA).

- Definition of recurrence: PSA ≥ 0.2 ng/mL on two consecutive measurements.

- Higher risk triggers: Levels above ~0.4-0.5 ng/mL, rapidly doubling, high Gleason score, positive margins, short time to PSA rise.

Conclusion

A “dangerous” PSA level after prostate removal depends on several factors—primarily how much PSA is present, how fast it rises, and patient-specific risks (pathology, margins, overall health). The common threshold for concern is a confirmed PSA ≥ 0.2 ng/mL, which defines biochemical recurrence in most guidelines. But earlier, smaller elevations (≥ 0.1 ng/mL) especially if persistent, with rapid doubling time, also merit attention.

If you or someone you know is monitoring PSA after prostatectomy, it’s important to work closely with the treating urologist/oncologist. They’ll interpret results in light of test sensitivity, pathology, and clinical context to decide if and when further treatment is needed.